During everyday life, I often encounter challenges that spark my curiosity and drive me to explore the world of technology. Recently, I faced one such challenge: a growing collection of garage remotes. The sheer number of these remotes led me to embark on an ambitious project to decipher the inner workings of these devices and create a device capable of opening up to six different garage doors.

This project has encompassed various areas, not just radio communications but also circuit design, battery optimization, and the art of low-level communication between integrated circuits.

Throughout this series of articles, we will delve into these five distinct yet interconnected segments:

- Basics of Radio Communications. (This article)

- Designing My First Remote Control. (Coming Soon)

- Opening My Garage Doors. (Coming Soon)

- Optimizing the Design for Minimal Size. (Coming Soon)

- A Guide for Building Your Own Multi-Door Remote. (Coming Soon)

Join me, as we explore the mysteries of remote control technology and modern electronics.

Transmitting Signals

Why Use Modulation

To begin analyzing radio signals, we must first understand how they work.

When I was a child, at my grandmother’s pool, we would sometimes try to create a “wave pool” using surfboards. To achieve this, we would push a surfboard up and down (my grandmother didn’t like this because the pool lost a lot of water).

Surely, my grandmother would have preferred us to make waves using our hands instead of surfboards; this way, the waves would have much less height:

The height of the waves is known as AMPLITUDE.

These waves would also be shorter:

The shorter a wave, the HIGHER the FREQUENCY.

They wouldn’t have been very fun for us because they wouldn’t have traveled very far, and they wouldn’t have filled the pool with waves like the surfboard did.

Electromagnetic radiation behaves very similarly: Instead of making waves in water, we are making waves in a dimension of the universe that we do not yet fully understand. Moreover, the waves in this dimension always travel at the speed of light.

Instead of using a surfboard or our hands to ripple this dimension of the universe, we shake electrons using an antenna. Just like in the pool, if our antenna is small, like the one in our mobile phone or garage remote, we won’t be able to create very long waves, meaning we won’t be able to transmit at a low frequency, as I did with the surfboard.

This animation, from the excellent video by 3Blue1Brown on electromagnetic radiation, shows how shaking an electron creates waves in the electromagnetic field.

Why Use Modulation

Imagine it’s nighttime, and you want to communicate with a friend from a long distance. You have a flashlight in your hand, so you can turn it on and off and send a series of pulses that your friend can interpret following a language you’ve agreed upon. Congratulations, you’ve just sent a message using ASK modulation, the same our remotes use.

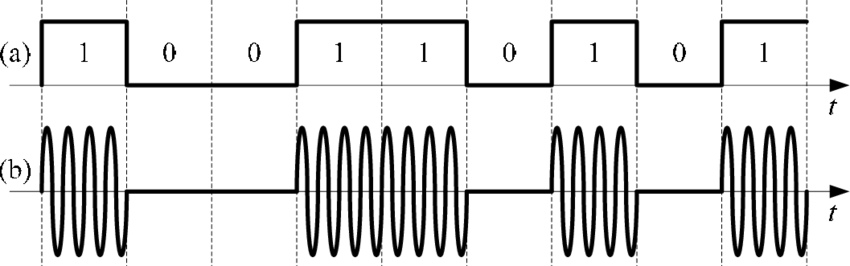

ASK stands for "Amplitude Shift Keying." This means we use changes in the height (AMPLITUDE) of the wave to communicate.

The following image shows how ASK modulation works:

As you can see, each light pulse is actually made up of many short waves. This is because our flashlight can’t create waves long enough for your friend to notice a single wave.

As you can see, each light pulse is actually made up of many short waves. This is because our flashlight can’t create waves long enough for your friend to notice a single wave.

Using short waves to transmit slower information is called MODULATION.

Designing a Language for Communication

Imagine we want to inform our friend of 4 things:

- Are we sleepy?

- Are we hungry?

- Are we scared?

- Do we need help?

The first idea you might have is that, for each question, if we want to say yes, we turn on the flashlight, and if we want to say no, we turn it off.

- We have to define how long we spend answering each question.

- If we want to say that we’re only hungry, we’ll only turn on the flashlight for a moment. But how will our friend know the flash is because we’re hungry and not because we need help? We would have to agree when the messages will be sent, meaning we each need a clock and keep it synchronized.

- We can’t send the message whenever we want; we have to wait for the agreed upon time to start transmitting.

- If our flashlight breaks, our friend will think everything is fine, and they won’t realize we can’t send more messages.

The next idea that would come to your mind is that every time we want to send a message, we can turn on the flashlight 4 times:

- If we want to say no, we’ll turn on the flashlight for a short while and leave it off for a longer while.

- If we want to say yes, we’ll turn on the flashlight for a long while and leave it off for a shorter while.

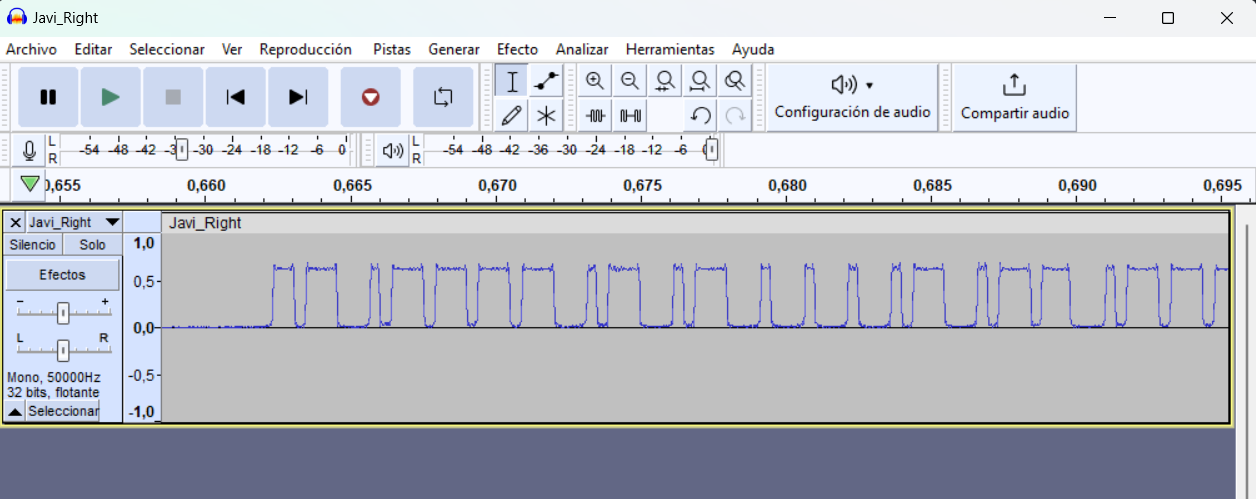

This way, we would solve all the problems we encountered with the first method. Our garage remotes use exactly the same language we just described, as we’ll see later.

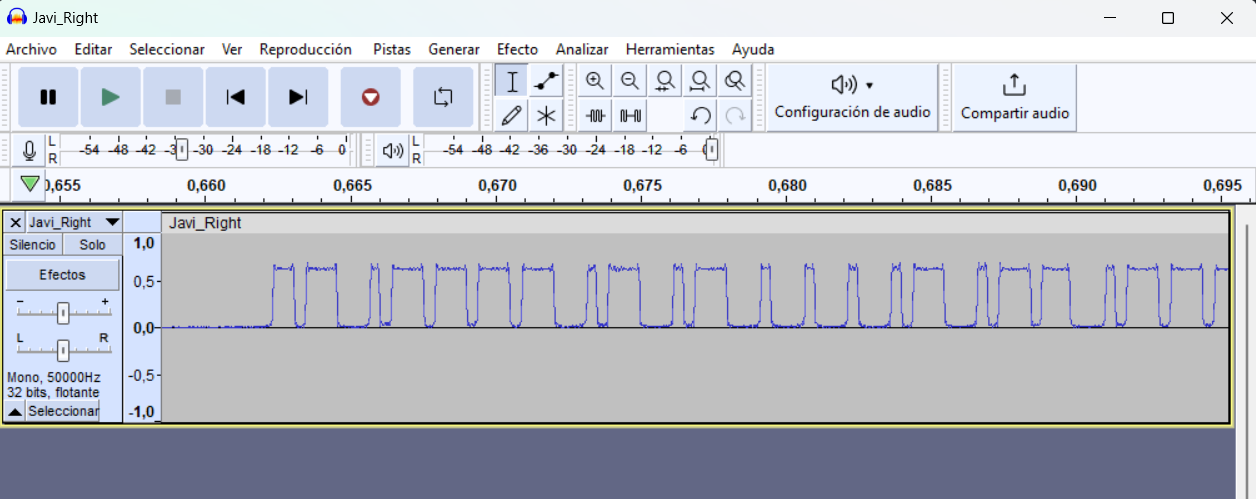

Image we’ll see later, showing the message sent by a garage remote.

Image we’ll see later, showing the message sent by a garage remote.

Receiving Signals

Your eyes are radio antennas

Humans have 6 receptors for electromagnetic waves, 3 in each of our eyes. These receptors physically detect the presence of a specific color, meaning waves with a specific length.

For example, the receptors for the color red filter waves with a length of about 700nm, as long as a bacterium. If we use a red flashlight, our friend will detect the pulses with 2 of their 6 receptors. A white flashlight emits a much more chaotic signal, it’s like splashing in the water.

The chaotic signal from the white flashlight is composed of many mixed waves and will activate all 6 receptors since, among others, it contains all the colors we can see.

Considering that you will live approximately 80 years according to the average life expectancy, you will live 2,524,608,000 seconds. If we want to reach 480,000,000,000,000 seconds, we would need to fill Camp Nou and Santiago Bernabéu stadiums to their maximum capacity. Red waves oscillate 480,000,000,000,000 times per second.

Seeing Multiple Colors at Once

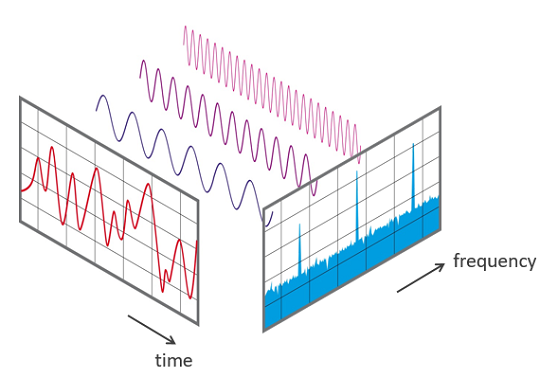

Today, we have a tool known as Software-Defined Radio (SDR), which allows us to detect the presence of multiple “colors” simultaneously using mathematics.

The most essential algorithm to achieve this is the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm, which breaks down received signals into their constituent frequencies, allowing us to see how much of each color is present in the light we are receiving. For example, if we analyze the light reflecting off an orange with FFT, we would see approximately twice as much red as green and almost no blue. Below, you can see an image summarizing how the Fourier transform works.

Why Can’t We See Remote Control Light?

The frequencies that make up visible light have disadvantages when it comes to controlling machines:

- They could be annoying: Imagine having to use a beam of light every time you want to control the TV; it could be annoying if you want to watch a movie in the dark.

- Waves of such high frequency (very short) have difficulty going through solid materials: Imagine if Wi-Fi only worked if you could see the router.

That’s why electronic devices typically use longer waves, colors that our eyes cannot detect, and our brains cannot imagine.

In Europe, automation predominantly communicates through ASK modulation with a single color defined by a 70cm long wave.

A 70cm wave has a frequency of 433.92 MHz, which means it oscillates 433,920,000 times per second. You could count to 433,920,000 in about 13 years.

Listening to Colors

SDR Sharp allows you to interpret signals in real-time and transform the information into sound pulses that you can hear, as long as they are within the range of human hearing. Additionally, you can export these demodulated signals as .wav files for detailed analysis using tools like Audacity.

My Remote Controls

Using the concepts mentioned earlier, I was able to start investigating what my remote controls were doing. For each of them, I pressed their buttons and waited to see a “color” in the program. If I had seen more than one separate “color” for any of the remotes, it would have meant they were using a slightly more complex modulation: Frequency Shift Keying (FSK).

FSK stands for "Frequency Shift Keying." This means we change the length of the waves to communicate (we change the color).

FSK modulation would involve using a green flashlight to indicate “yes” and a red flashlight to indicate “no.” Fortunately, none of my remote controls did this, which means they all use the simpler ASK.

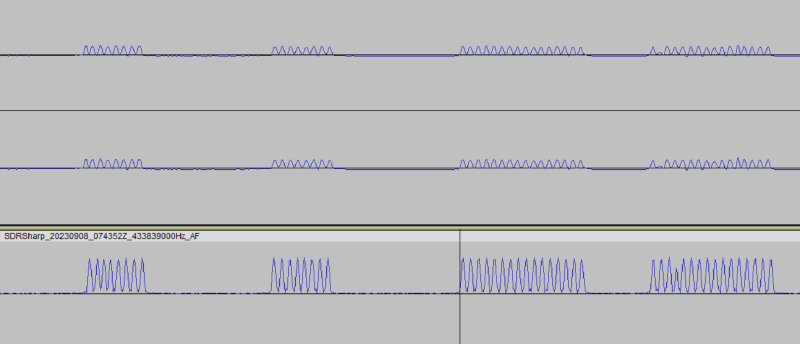

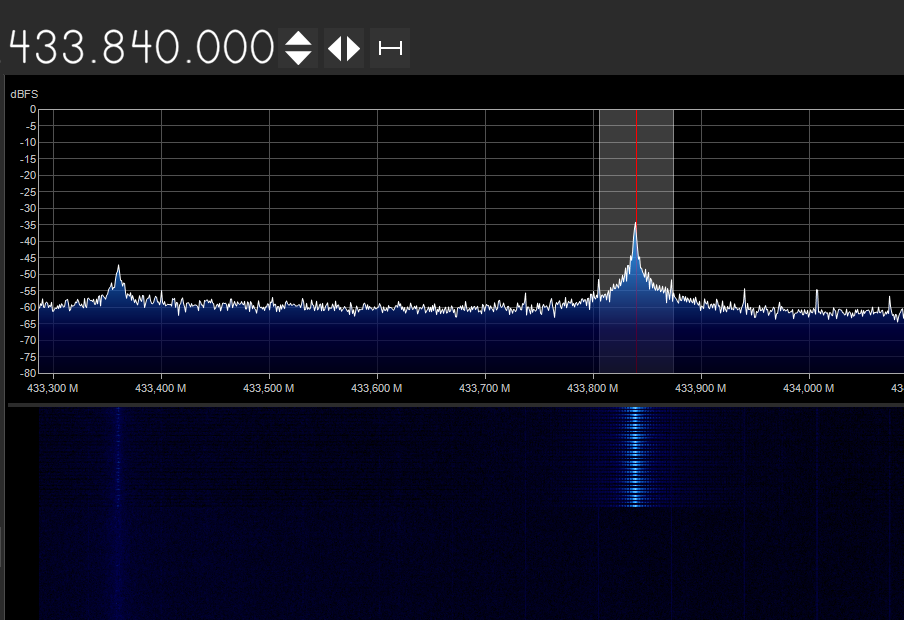

In this image, you can see what a remote control looks like in SDR Sharp. If we set the demodulation to ‘AM’ mode and select the “color” we’re interested in, we can hear the pulses in the signal.

In another image, you can see what the .wav recording looks like in Audacity. Finally, we can observe the information sent by the remote control.

Three of the four remotes I have use a 70cm wave, a color we can’t see. However, one of the remotes, due to its age, uses 1m waves, a color (or frequency) that regulations have prohibited for enthusiasts since then.

A fun fact: in the past, professional telegraph operators referred to amateurs as ‘ham-fisted’ due to their tendency to make mistakes in their messages. This eventually led to the frequency bands where amateurs have legal permission to operate being called ‘Ham-Bands.’

I remain determined to explore the territory of 1m waves (280MHz frequency), the biggest setback is the difficulty to find a device that will emit this “color”. Stay tuned for updates on this intriguing quest.

Conclusion

And with that, we conclude our initial journey into the fascinating world of RF signals and their modulation/demodulation. These insights lay the foundation for our upcoming adventures. In the next articles, we’ll leverage this knowledge to create our own multi-door garage remote control, providing a practical demonstration of the concepts we’ve discussed. So, stay tuned for the next installment, where we’ll dive into designing the first proof of concept.

For Further Exploration

If you want to learn more about electromagnetic radiation and visible light, I recommend these videos:

- This demo surprised me (a lot) | Barber pole, part 1 by 3Blue1Brown, where he presents a visual phenomenon that exposes interesting properties of light.

- The origin of light, scattering, and polarization | Barber pole, part 2 also by 3Blue1Brown, where he starts explaining the concepts behind the previously seen phenomenon to understand it intuitively.

To learn more about the Fourier Transform, I recommend these videos:

- The Remarkable Story Behind The Most Important Algorithm Of All Time by Veritasium, discussing the history and importance of this algorithm.

- But what is the Fourier Transform? A visual introduction. by 3Blue1Brown, useful for understanding what’s happening behind the scenes.